Kakawin of Clayoquot Sound: Stories & Insights

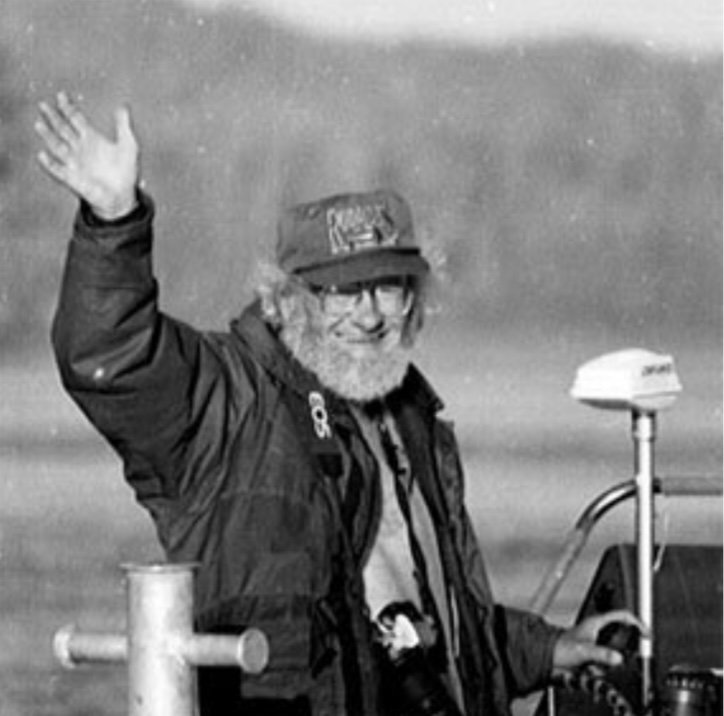

/photo by Andrew McCurdy. You can find Andrew's photography (available for purchase) on his Instagram: @lonelyspruce.

You can also win this print by entering our raffel at The ucluelet brewery or surf sisters! Tickets are 5$ and PROCEEDS go towards supporting our work in marine mammal research, education and rescue.

February 11, 2021. Dive Log. Aline Carrier.

“We look and there’s the surge channel that goes on the other side, the open pacific side. And we are like, oh the tide is high enough that there is some water so we can swim through that surge channel. And it's flat, flat, flat. So we're like lets go see, I’ve never been there.

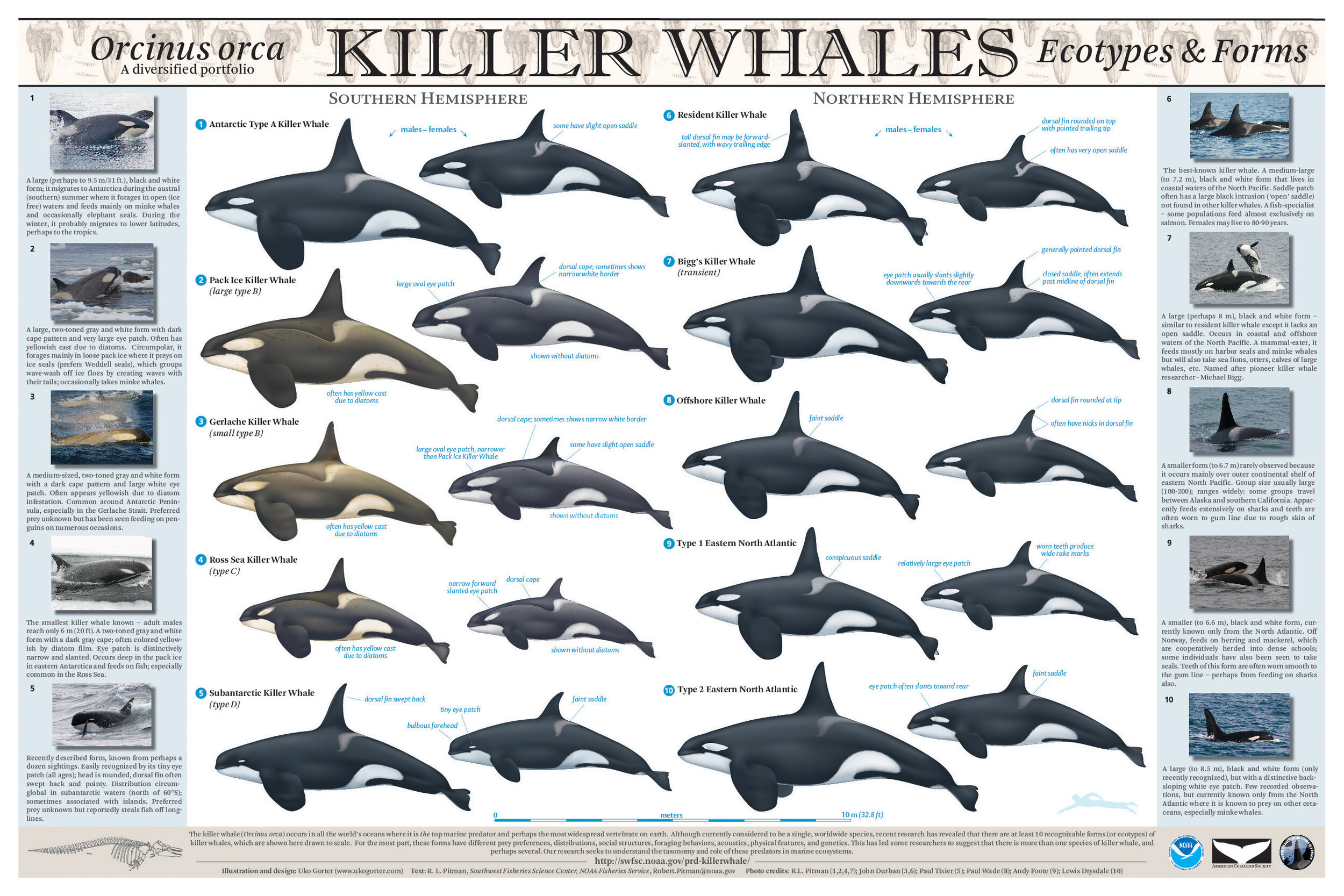

So we went over, and on the other side it's one of the biggest sea urchin barrens I have ever seen. It’s just sea urchins. It looks like a big dessert. And because I love sea urchins one of the first things I did was swim down to take some sea urchins. I was having a lot of fun. I was putting them on my hands and then you know, when you swim back up and you flip your hands over they stick. So I was kind of joking like this and showing Andrew, ‘Oh look at this Andrew’ and laughing. Andrew was like, ‘No, Aline Orcas, Orcas!’ and I was like, ‘No, Sea Urchins!’. Then Andrew was like ‘No ORCAS!’, and I just remember thinking No. I realized what he was saying and I was just refusing, because this is my biggest nightmare actually to see some orcas while swimming. So I’m just thinking No and then he’s looking BEHIND me, and I’m like No, No No. Then as I turn, I see that dorsal fin coming up at the surface of the water fully out and it’s like four, five meters high and it’s so huge and then it comes down, coming towards me.

In my head I’m like, ok that’s it, if I’m about to get munched on by an Orca at least I wanna see it. So I put my head in the water. I don’t even know if I had my snorkel. I don’t even know if I took the time to breathe before. I just know that I put my head in the water, and then I saw them. And somehow I knew there were four, and they passed right in front of me. They just swam and I was expecting it to be kind of loud and painful, because I was expecting them to eat me. I was expecting some form of impact but it was totally the opposite. It went super quiet, super calm, even if it was fast it seemed like it was slowing down and everything was holding up in time and it was just there. And then they swam away and disappeared, as fast as it happened they disappeared.”

This story is one of many wondrous orca encounters shared in our new eBook, highlighting our community's connection with these awe inspiring animals.

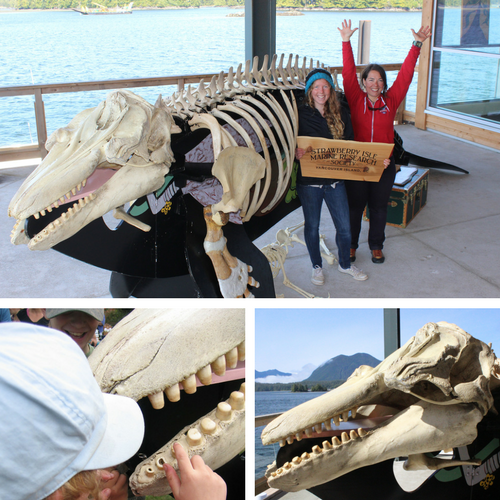

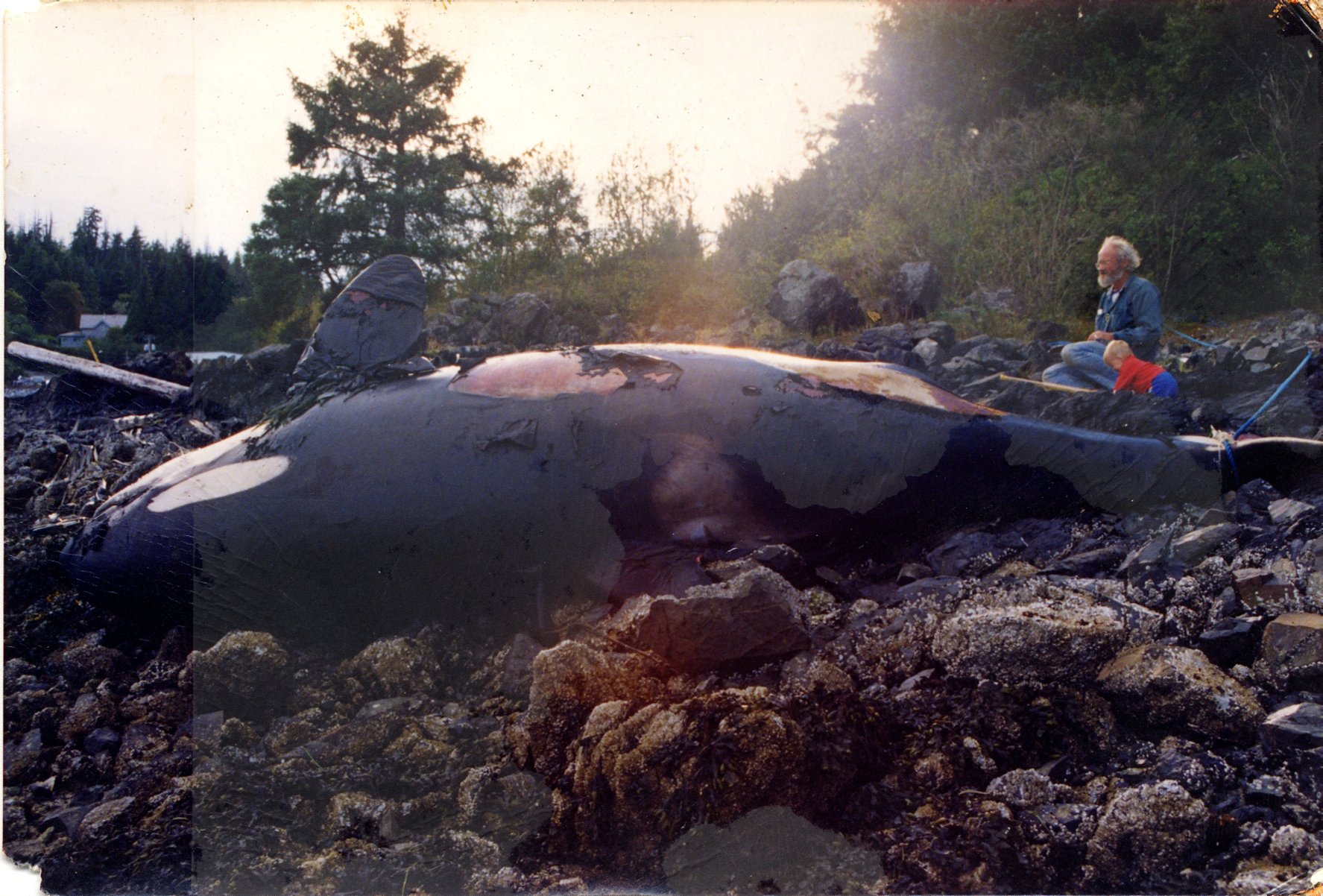

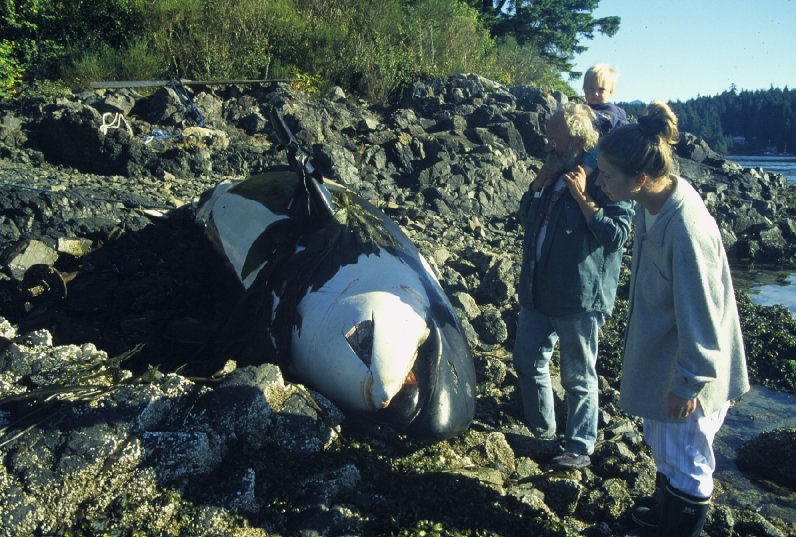

Photos by (left to right) W. C. Barnes, Danny O'Farrell, Sydney Dixon & Jeremy Mathieu